Last Updated on November 13, 2025 by Vlad

The samurai shaped Japanese history for over 700 years, from the 12th century until the Meiji Restoration in 1868. These warriors followed Bushido – the way of the warrior – a code emphasising loyalty, honour, and martial skill. But the reality was more complex than the romanticised image suggests. Some samurai were brilliant strategists who unified a fractured nation. Others were ruthless warlords who burnt temples and slaughtered thousands. Many were both.

What surprised me most during my visits to Japanese castles and museums isn’t just the military history – it’s how these warriors influenced everything from tea ceremony to landscape design, from politics to philosophy. Their legacy goes far beyond the battlefield.

This guide covers 25 of the most significant samurai in Japanese history, including five women warriors who fought alongside men and sometimes led armies. I’ve organised them by their historical role rather than chronological order, which makes their impact on Japan’s development clearer.

Samurai Warriors at a Glance

Compare 20 legendary warriors by era, specialty, and achievements

| Name | Years | Era | Domain/Region | Specialty | Primary Achievement |

|---|

The Three Unifiers of Japan

The late 16th century saw Japan torn apart by constant warfare between feudal lords (daimyō). Three successive leaders – often called the “Three Unifiers” – gradually brought the country under centralised control. A Japanese saying captures their different approaches: “If the cuckoo doesn’t sing, Nobunaga kills it, Hideyoshi makes it sing, and Ieyasu waits for it to sing.”

Oda Nobunaga (1534-1582)

Nobunaga began Japan’s unification through innovation and brutal efficiency. He was among the first daimyō to recognise the military potential of firearms, which Portuguese traders had introduced to Japan. His use of ashigaru (foot soldiers with guns) broke the traditional dominance of mounted samurai.

Major Achievements:

- Defeated the powerful Imagawa clan at the Battle of Okehazama (1560) despite being outnumbered 10 to 1

- Controlled central Japan by the 1570s through strategic castle building and innovative tactics

- Promoted economic policies that increased trade and weakened rival domains

The Controversial Reality: Nobunaga’s brutality often gets downplayed in popular history. In 1571, he surrounded Enryaku-ji, a Buddhist monastery on Mount Hiei, and burnt it to the ground with everyone inside – killing between 3,000 and 4,000 monks, women, and children. His justification was that the monastery had supported his enemies, but the massacre shocked even his contemporaries.

He never lived to see Japan unified. In 1582, one of his own generals, Akechi Mitsuhide, betrayed him. Trapped at Honnō-ji temple in Kyoto, Nobunaga committed seppuku (ritual suicide) rather than face capture.

Where to Visit:

- Nagoya Castle – Built in Nobunaga’s home territory

- Azuchi Castle ruins (Shiga Prefecture) – His revolutionary castle design influenced all subsequent Japanese castles, though only the stone foundations remain

Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1537-1598)

Hideyoshi’s story is remarkable because he achieved what was theoretically impossible: he rose from peasant origins to rule all of Japan. The rigid class system should have prevented this entirely, but Hideyoshi’s intelligence and military talent brought him to Nobunaga’s attention.

After Nobunaga’s death, Hideyoshi avenged his master by defeating the traitor Akechi Mitsuhide within 11 days. He then outmanoeuvred Nobunaga’s other generals to become his successor, completing the unification Nobunaga had started.

Major Achievements:

- Completed the unification of Japan by 1590

- Conducted land surveys that formed the basis of taxation for centuries

- Implemented the sword hunt, disarming peasants and solidifying the class system (ironically, given his own origins)

The Failed Invasions: Hideyoshi’s invasions of Korea (1592-1598) were catastrophic failures that wasted resources and lives. His judgment deteriorated late in life, possibly due to illness or the influence of yes-men around him. These invasions ultimately weakened his clan, making it easier for Tokugawa Ieyasu to seize power after his death.

Where to Visit:

- Osaka Castle – Hideyoshi’s magnificent powerbase (rebuilt in 1931, but still impressive)

- Sanjūsangen-dō Temple, Kyoto – Hideyoshi rebuilt this after the 1596 earthquake

Tokugawa Ieyasu (1543-1616)

If Nobunaga was the bold revolutionary and Hideyoshi the ambitious climber, Ieyasu was the patient strategist who waited for his moment. He spent decades as a second-tier power, nominally serving first Nobunaga, then Hideyoshi, all while quietly building his strength.

His patience paid off. After Hideyoshi’s death, Ieyasu defeated his rivals at the Battle of Sekigahara in 1600 – one of the most decisive battles in Japanese history. In 1603, he became shōgun, establishing the Tokugawa shogunate that would rule Japan until 1868.

Major Achievements:

- Founded a dynasty that ruled Japan for 265 years

- Established Edo (modern Tokyo) as the political capital

- Implemented the sankin-kōtai system, forcing daimyō to maintain residences in Edo, which kept them under control and drained their finances

- Initiated Japan’s isolation policy, restricting foreign contact

Why He Succeeded: Ieyasu understood that power came from patience and strategic thinking, not just military victory. He let others make the first move, then capitalised on their mistakes. His government brought unprecedented stability and peace to Japan, though at the cost of social rigidity and international isolation.

Where to Visit:

- Nikkō Tōshō-gū Shrine – His ornate mausoleum (a day trip from Tokyo I highly recommend). This stunning UNESCO World Heritage Site is one of Japan’s most impressive shrine complexes, with intricate carvings covered in gold leaf.”

- Edo Castle site (Imperial Palace grounds, Tokyo) – The fortress that became Japan’s political centre

- Kunōzan Tōshō-gū Shrine (Shizuoka) – His initial burial site

Japanese Samurai Warriors Timeline

Spanning over 700 years of history (1159-1932)

The Greatest Samurai Warriors

These samurai earned their reputation through exceptional skill in combat, innovative tactics, or undefeated records. Their martial abilities remain legendary.

Miyamoto Musashi (c. 1584-1645)

Musashi is the most famous samurai internationally, and for good reason. He developed a two-sword fighting style (niten’ichi-ryū), fought in over 60 duels, and never lost. His most famous duel was against Sasaki Kojirō at Ganryū Island in 1612.

But Musashi was more than just a swordsman. He was a philosopher, painter, and calligrapher. His book “The Book of Five Rings” (Go Rin no Sho) is studied worldwide, not just by martial artists but by business strategists and military tacticians.

The Ganryū Island Duel: The story of Musashi’s duel with Kojirō is famous, but the details matter. Musashi arrived late – some say deliberately, to anger Kojirō. He carved a wooden sword (bokken) from an oar on the boat ride over, using its extra length to his advantage against Kojirō’s famously long blade. He won with a single strike.

Some historians question whether this really demonstrates honour or just clever psychology. Musashi himself wrote that in battle, any advantage is worth taking.

Where to Visit:

- Kokura Castle (Fukuoka) – Near where the famous duel took place

- Musashi Museum (Kumamoto) – Dedicated to his life and works

Takeda Shingen (1521-1573)

Takeda Shingen was a military genius known for his cavalry tactics and his legendary rivalry with Uesugi Kenshin. He fought over 40 battles and was rarely defeated. Most significantly, he was the only person to defeat Tokugawa Ieyasu in battle (at Mikatagahara in 1572).

Why He Matters: In my view, Shingen was the only daimyō capable of stopping Ieyasu from eventually ruling Japan. His death from illness in 1573 changed the course of Japanese history. Had he lived another decade, Ieyasu might never have risen to power.

The Takeda cavalry was feared throughout Japan. Shingen’s “wind, forest, fire, and mountain” battle standard (Fūrinkazan) captured his tactical philosophy: “Swift as the wind, quiet as the forest, fierce as fire, immovable as the mountain.”

The Shingen-Ko Festival: Every April, Yamanashi Prefecture holds the Shingen-Ko Festival, featuring the world’s largest gathering of samurai re-enactors. Over 1,000 participants dress in period armour and recreate Shingen’s battles. The locals still revere Shingen nearly 450 years after his death. Read my complete Yamanashi travel guide for more on visiting this region and planning around the festival.

Where to Visit:

- Takeda Shrine (Kofu, Yamanashi) – Built on the site of his former residence

- Shingen-Ko Festival (April) – Annual celebration with massive samurai parade

Uesugi Kenshin (1530-1578)

Uesugi Kenshin is remembered as Takeda Shingen’s great rival and equal. They fought five major battles at Kawanakajima between 1553 and 1564, with no decisive victor. Japanese historians still debate who was the superior tactician.

What made Kenshin unusual was his devotion to Buddhism and his reputation for honour. He reportedly sent salt to Shingen’s domain when rival lords cut off their supply, saying that warriors should fight on the battlefield, not through economic warfare. Whether this actually happened or is romanticised myth remains debatable.

Where to Visit:

- Kasugayama Castle ruins (Niigata Prefecture) – His primary stronghold

- Uesugi Shrine (Yonezawa, Yamagata) – Contains many of his relics

Honda Tadakatsu (1548-1610)

Tadakatsu was Tokugawa Ieyasu’s most trusted general and participated in over 100 battles without receiving a significant wound. Both Oda Nobunaga and Toyotomi Hideyoshi praised his abilities, with Hideyoshi calling him “the warrior who surpassed even the Warring States period.”

His loyalty to Ieyasu was absolute, and his military skill helped secure Ieyasu’s victories, including the crucial Battle of Sekigahara. He represents the ideal of the perfect samurai retainer – loyal, skilled, and disciplined.

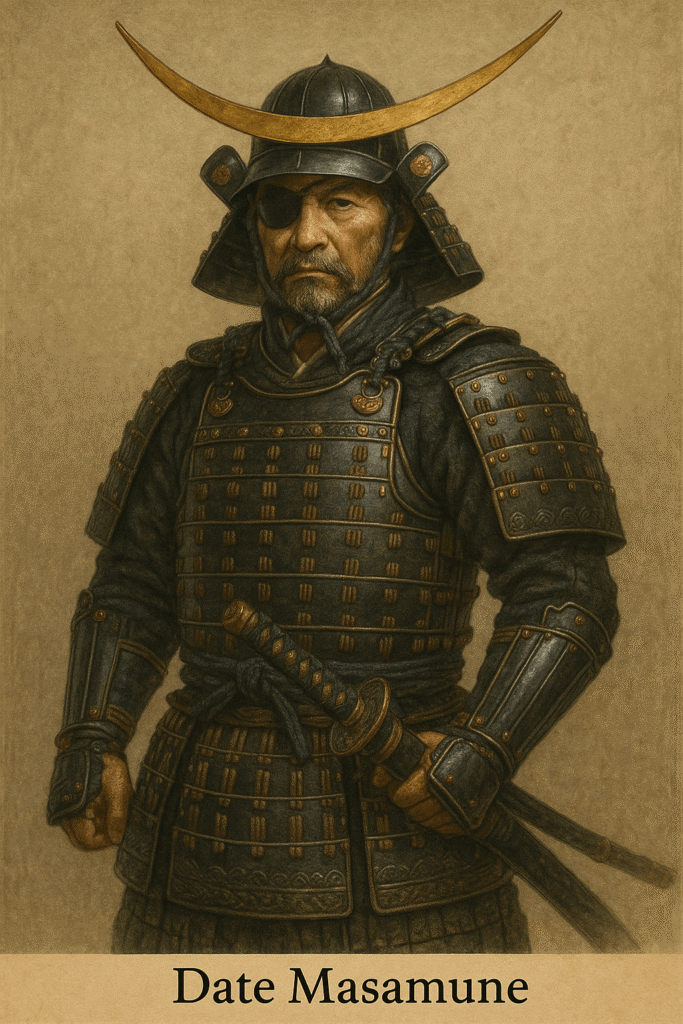

Date Masamune (1567-1636)

Known as the “One-Eyed Dragon” after losing his right eye to smallpox as a child, Date Masamune was a formidable warrior and administrator who built Sendai into a major city. He was ambitious and cunning, expanding his territory through both military conquest and political marriages.

What sets Masamune apart was his international outlook. He sent a diplomatic mission to the Vatican in 1613 (the Keichō Embassy), making him one of the few Japanese leaders of his era to engage with the Western world. Had he been born earlier, he might have competed for national leadership, but he came of age just as Hideyoshi was consolidating power.

Where to Visit:

- Sendai Castle ruins (Miyagi Prefecture) – His powerbase

- Zuihōden Mausoleum (Sendai) – His ornate burial site

Sanada Yukimura (1567-1615)

Sanada Yukimura is celebrated for his heroic last stand during the Siege of Osaka in 1615. He commanded the defence of Osaka Castle against Tokugawa forces, knowing the battle was likely hopeless. His “Sanada’s Ten Braves” (likely fictional elite guards) have become legendary in Japanese culture.

He was killed in battle after nearly breaking through to Tokugawa Ieyasu’s position. Tokugawa Ieyasu himself supposedly praised Yukimura as “the best warrior in Japan” after the battle.

Where to Visit:

- Sanada Museum (Nagano) – Dedicated to the Sanada clan

- Osaka Castle – Site of his final battle

Hattori Hanzō (1542-1596)

Hattori Hanzō, known as “Devil Hanzō,” was both samurai and ninja who served Tokugawa Ieyasu. His most famous achievement was helping Ieyasu escape through hostile Iga Province after Oda Nobunaga’s assassination, securing Ieyasu’s survival and eventual rise to power.

Hanzō’s reputation has been heavily romanticised in popular culture, but he was genuinely skilled in espionage, guerrilla warfare, and unconventional tactics. He commanded a unit of ninja from Iga Province and served as Ieyasu’s security chief.

Where to Visit:

- Sainen-ji Temple (Tokyo) – His grave site

- Hanzōmon Gate (Imperial Palace, Tokyo) – Named after him

The Tragic Heroes

These samurai fought bravely but ultimately died in defeat, often betrayed or overwhelmed by circumstances beyond their control. Japanese culture particularly celebrates their loyalty despite the impossible odds they faced.

Minamoto no Yoshitsune (1159-1189)

Yoshitsune is one of Japan’s most beloved tragic heroes. He was a brilliant military commander during the Genpei War, securing decisive victories that led to the Minamoto clan’s triumph and the establishment of the Kamakura shogunate. His most famous victory was the naval Battle of Dan-no-ura in 1185, which destroyed the Taira clan.

The Tragedy: His own brother, Minamoto no Yoritomo (the first shōgun), grew jealous and suspicious of Yoshitsune’s popularity and military success. Yoritomo forced Yoshitsune to flee and eventually ordered his death. Yoshitsune committed seppuku in 1189, betrayed by the brother he had fought to empower.

His story has been retold countless times in Japanese literature, theatre, and film—the loyal warrior brought down by political jealousy.

Kusunoki Masashige (1294-1336)

Kusunoki Masashige represents absolute loyalty to the emperor. He was a brilliant tactician who used guerrilla warfare and unconventional strategies to support Emperor Go-Daigo’s attempt to overthrow the Kamakura shogunate.

At the Battle of Minatogawa in 1336, Masashige knew he was facing overwhelming odds but refused to retreat when the emperor ordered him to fight. He and his brother committed seppuku after the battle rather than flee. His final words were reportedly, “Seven times I wish to be reborn to destroy the enemies of the Emperor.”

During World War II, the militarist government heavily promoted Masashige’s story as an example of absolute loyalty. Today, historians view his legacy more critically, but he remains a powerful symbol of samurai devotion.

Where to Visit:

- Minatogawa Shrine (Kobe) – Built in his honour

Ishida Mitsunari (1560-1600)

Ishida Mitsunari was a capable administrator under Toyotomi Hideyoshi who led the Western Army against Tokugawa Ieyasu at the Battle of Sekigahara. His defeat in this battle marked the end of the Sengoku period and the beginning of the Tokugawa shogunate.

Mitsunari was more skilled as an administrator than as a military commander, and his rigid adherence to principle made him political enemies. When several of his allies defected during the Battle of Sekigahara, his army collapsed. He was captured and executed in Kyoto.

Shimazu Yoshihiro (1535-1619)

Yoshihiro fought on the losing side at Sekigahara but executed one of the most famous retreats in military history. Rather than flee, he ordered a direct charge through the enemy centre, breaking through Tokugawa lines and fighting his way back to his home domain of Satsuma. His tactical brilliance in retreat is still studied by military historians.

Despite being on the losing side, Tokugawa Ieyasu allowed Yoshihiro to keep his domain, respecting his martial skill and the difficulties of conquering distant Satsuma.

Women Samurais Who Fought Like Hell

Female samurai warriors (onna-bugeisha) were trained in martial arts, particularly the naginata (pole weapon), and fought to defend their homes and clans. While less common than male samurai, these women proved equally skilled and brave in combat.

Tomoe Gozen (c. 1157-1247)

Tomoe Gozen is the most famous female samurai, described in “The Tale of the Heike” as “a remarkably strong archer, and as a swordswoman she was worth a thousand warriors.” She fought in the Genpei War alongside Minamoto no Yoshinaka and was known for her skill in horseback archery and close combat.

During the Battle of Awazu in 1184, she reportedly took the head of a famous warrior in single combat. Accounts differ on what happened next—some say Yoshinaka ordered her to flee and save herself, others say she survived the battle and later became a nun.

Nakano Takeko (1847-1868)

Nakano Takeko led an unofficial unit of female warriors during the Boshin War. When the imperial army attacked Aizu domain, she formed the Jōshitai (Women’s Army) and fought with a naginata despite not having official permission to join the battle.

She was shot in the chest during the Battle of Aizu in 1868. Dying, she asked her sister to cut off her head so it wouldn’t become a trophy for enemy forces. She was 21 years old. Her courage made her a symbol of resistance in the final days of the samurai era.

Where to Visit:

- Hōkai-ji Temple (Aizu, Fukushima) – Her grave, beneath a pine tree she loved

Hangaku Gozen (c. 1190s)

Hangaku (also called Itagaki) was a warrior during the early 13th century who commanded the defence of Torisakayama Castle during a siege. She led approximately 3,000 warriors against an attacking force of 10,000 during the Kennin Uprising in 1201.

She was skilled in archery and fought until she was wounded and captured. Rather than being executed, she was pardoned and later married one of her captors—an unusual outcome that suggests the respect she earned through her military skill.

Lady Mochizuki (16th century)

Lady Mochizuki was a 16th-century warrior who played a crucial role during the Siege of Shiroishi Castle. She led a night attack of female warriors against the Takeda clan’s forces, which helped secure victory for her clan.

Less is documented about her life than other female samurai, but her leadership during the siege demonstrates that women warriors weren’t just defending their homes – they were actively planning and executing military operations.

Yamamoto Yae (Yae Niijima) (1845-1932)

Yae grew up in Aizu domain, where martial training for women was encouraged. She became skilled in both the naginata and firearms – unusual for women at the time. During the Boshin War, she fought in the defence of Aizu, using a Spencer rifle.

After the war, she adapted remarkably to the changing times. She became a nurse, converted to Christianity, and married Jo Niijima, founder of Doshisha University. She later worked at the Red Cross and lived until 1932, bridging the samurai era and modern Japan.

Her life demonstrates the resilience of the samurai spirit beyond warfare—the ability to adapt while maintaining personal principles.

Where to Visit:

- Aizu Bukeyashiki (Fukushima) – Samurai residence museum that covers onna-bugeisha history

Other Notable Samurai

Sakamoto Ryōma (1836-1867)

Ryōma was a visionary who helped overthrow the Tokugawa shogunate and pave the way for the Meiji Restoration. Born into the samurai class, he rejected traditional samurai values in favour of modernisation, advocating for democracy, a modern navy, and economic reform.

He negotiated the crucial Satchō Alliance between rival domains, which provided the military strength to challenge the shogunate. He was assassinated in 1867 at age 31, just before seeing his vision realised.

Where to Visit:

- Katsurahama Beach (Kochi) – Site of his statue overlooking the Pacific

- Ryōma Museum (Kochi) – Comprehensive museum about his life

Katō Kiyomasa (1562-1611)

Kiyomasa was one of Toyotomi Hideyoshi’s most trusted generals, known for his strict adherence to samurai values and his architectural achievements. He built or renovated several castles, including parts of Nagoya Castle and the impressive Kumamoto Castle.

He played a significant role in the invasions of Korea, where his military skills were evident but also where he participated in the brutality that characterised those campaigns.

Where to Visit:

- Kumamoto Castle – His architectural masterpiece

Maeda Toshiie (1538-1599)

Toshiie was one of Oda Nobunaga’s leading generals, known for his skill with the yari (spear). After Nobunaga’s death, he supported Toyotomi Hideyoshi and governed Kaga Domain, making it one of the richest domains in Japan.

His rule was marked by economic prosperity and cultural development, showing how samurai leadership extended beyond military prowess.

Fukushima Masanori (1561-1624)

Masanori served under both Oda Nobunaga and Toyotomi Hideyoshi, fighting in numerous important battles. He was known for his bold, sometimes reckless nature, which occasionally put him at odds with his superiors.

After the establishment of the Tokugawa shogunate, his failure to comply with shogunate regulations led to reduction of his domain, reflecting how the peaceful Edo period had different requirements than the warring era.

Chōsokabe Motochika (1539-1599)

Motochika unified the island of Shikoku under his rule, showing remarkable military and administrative skill. His reign was marked by constant warfare as he attempted to expand beyond Shikoku, but he ultimately submitted to Toyotomi Hideyoshi.

His story reflects the ambitions and limitations of regional daimyō during the unification period.

Sasaki Kojirō (late 16th-early 17th century)

Kojirō was a highly skilled swordsman famous for his technique “Tsubame Gaeshi” (Swallow Return) and his unusually long sword. He is most remembered for his duel with Miyamoto Musashi at Ganryū Island, which he lost.

Kojirō represents the tragic figure in Japanese culture—a master swordsman who fell to an even greater warrior. His duel with Musashi has been depicted countless times in literature, film, and art.

Where to Experience Samurai History in Japan

Understanding samurai history is one thing; experiencing it is another. Here are the best places to connect with Japan’s samurai heritage:

Castles with Original Structures

Himeji Castle (Hyōgo Prefecture) The most beautiful and well-preserved original castle in Japan. Never destroyed in war or natural disaster, it offers the most authentic castle experience. The white exterior earned it the nickname “White Heron Castle.” It’s also a UNESCO World Heritage Site, and deservedly so.

- Getting there: 1 hour from Kyoto, day trip from Osaka

- Entry: ¥1,000 adults

Matsumoto Castle (Nagano Prefecture) One of only five castles with original keeps, this stunning black castle sits against the backdrop of the Japanese Alps.

- Getting there: 2.5 hours from Tokyo

- Entry: ¥700 adults

Hikone Castle (Shiga Prefecture) Another original castle with beautiful grounds and lake views. Way less crowded than Himeji.

- Getting there: 45 minutes from Kyoto

- Entry: ¥800 adults

Museums and Cultural Sites

Tokyo National Museum (Ueno, Tokyo) The most comprehensive collection of samurai armour, weapons, and artefacts in Japan. Easier to visit than travelling to multiple castles.

- Entry: ¥1,000 adults

- Getting there: Ueno Station

Samurai Museum (Shinjuku, Tokyo) Smaller and more touristy, but excellent if you’re travelling with kids. They offer armour try-on experiences.

- Entry: ¥1,900 adults

- Getting there: 5 minutes from Shinjuku Station

The Sword Museum (Token Hakubutsukan) (Ryōgoku, Tokyo) For those fascinated by Japanese swords, this specialised museum displays some of the finest blades ever made.

- Entry: ¥1,000 adults

- Getting there: Ryōgoku Station

Aizu Bukeyashiki (Fukushima) A reconstructed samurai residence that covers daily life, including the history of onna-bugeisha. This is where I’d recommend if you want to understand how samurai actually lived.

- Entry: ¥850 adults

- Getting there: Day trip from Tokyo (2.5 hours)

Festivals and Events

Shingen-Ko Festival (Kofu, Yamanashi) – Early April. The world’s largest samurai festival with over 1,000 participants in period armour recreating Takeda Shingen’s battles.

- Getting there: 2 hours from Tokyo

Soma Nomaoi (Fukushima) – Late July. A thousand-year-old festival featuring samurai horseback archery and cavalry demonstrations.

Jidai Matsuri (Kyoto) – October 22. Historical parade featuring participants dressed as famous samurai and other figures from Japanese history.

Day Trips from Tokyo

Most of these samurai sites are accessible as day trips from Tokyo:

- Nikkō (2 hours) – Tokugawa Ieyasu’s shrine

- Kamakura (1 hour) – Former samurai capital with museums

- Odawara (1.5 hours) – Castle and samurai history

- Kofu, Yamanashi (2 hours) – Takeda Shingen sites

Frequently Asked Questions

Who was the greatest samurai warrior?

This depends on how you define “greatest.” Miyamoto Musashi never lost a duel, making him arguably the best swordsman. Tokugawa Ieyasu was the most successful politically, founding a dynasty that lasted 265 years. Takeda Shingen was possibly the best battlefield commander. There’s no single answer.

Were samurai only men?

No. Women warriors called onna-bugeisha trained in martial arts and fought in battles, particularly when defending castles. They typically specialised in the naginata (pole weapon) rather than swords. DNA testing of battlefield remains suggests female participation in combat was higher than historical records indicated.

Did samurai really commit seppuku (ritual suicide)?

Yes. Seppuku was considered an honourable death when facing capture, after failure, or to follow a lord in death. The practice involved cutting one’s abdomen, and a trusted assistant would perform kaishaku (decapitation) to end suffering quickly. It was brutal but seen as demonstrating courage and taking responsibility.

What happened to the samurai class?

The Meiji Restoration (1868) gradually abolished the samurai class. The government banned wearing swords in public (1876), eliminated samurai stipends, and established a modern conscript army. Many samurai became part of the new government, military, or police force. Others struggled to adapt to the changed world.

Can you see real samurai armour in Japan?

Yes, extensively. Most major castles have museums displaying authentic armour, weapons, and artefacts. The Tokyo National Museum has one of the best collections. Many pieces are 400-500 years old and in excellent condition.

What’s the difference between samurai and ninja?

Samurai were the warrior nobility who fought openly according to Bushido principles. Ninja (shinobi) were espionage agents and guerrilla fighters who used stealth, deception, and unconventional tactics. Some individuals, like Hattori Hanzō, functioned as both. Hollywood has exaggerated the differences and ninja capabilities considerably.

What should I read or watch to learn more?

Books:

- “The Book of Five Rings” by Miyamoto Musashi (primary source)

- “Samurai: A Military History” by Stephen Turnbull (academic but readable)

- “Musashi” by Eiji Yoshikawa (historical fiction, but excellent)

Films:

- “Seven Samurai” (1954) by Akira Kurosawa – The essential samurai film

- “Harakiri” (1962) – Shows the darker reality behind samurai honour

- “The Twilight Samurai” (2002) – About low-ranking samurai struggling with poverty

Were samurai as honourable as their reputation suggests?

Sometimes, but the reality was complex. The Bushido code existed, but samurai also committed massacres, betrayed allies, and pursued political power ruthlessly. The romanticised image of the honourable samurai was partly created during the Edo period when actual warfare had ended, and later promoted during the Meiji period and World War II for nationalistic purposes.

Many samurai did demonstrate extraordinary loyalty and courage, but they were also products of a violent feudal system. It’s important to understand both the admirable aspects and the historical realities.

How much does it cost to visit samurai sites in Japan?

Castle entry fees typically range from ¥500-¥1,000 (roughly $5-$10 AUD). Museums are similar. The major expense is usually transport, though sites near Tokyo, Kyoto, and Osaka are easily accessible by train. Budget roughly ¥3,000-¥5,000 per day trip including transport, entry fees, and meals.

Is it worth visiting multiple castles?

If you’re particularly interested in samurai history, yes. Each castle has different architecture and history. However, if you only have time for one, I’d recommend either Himeji (most impressive original) or Osaka (central to unification history). The reconstructed castles often have better museums but lack the authentic feel.

Final Thoughts

The samurai era ended over 150 years ago, but these warriors continue to shape how we understand honour, discipline, and loyalty. Their legacy appears in everything from modern martial arts to business philosophy, from films to literature.

What strikes me after visiting numerous castles and museums across Japan is how human these legendary figures were. They weren’t infallible heroes – they made mistakes, betrayed allies, and sometimes died in foolish battles. But many also demonstrated remarkable courage, strategic brilliance, and commitment to principles even when facing death.

Whether you’re fascinated by military history, interested in Japanese culture, or planning to visit Japan’s castles and museums, understanding these historical figures adds depth to the experience. The stones of Japanese castles have witnessed centuries of warfare, political intrigue, and the slow transformation from feudal society to modern nation. That history is still visible if you know where to look.